Note: If you registered before 16 October 2017 and have not yet done so please reset your password. Reset

We have switched over to a new website platform which will allow us to vastly improve the service offered by The Talent Bank.

How to Write Poetry For Beginners: Easy if You Know How

Many people seem to have a fear of poetry.

Perhaps they were taught badly in school by teachers who themselves feared poetry or perhaps they believe poetry is for clever people, pretentious people – or just strange people!

But poetry has no more need to be elitist and obscure than a lemon cake has to contain chocolate.

Writing poetry may seem impossible for beginners but it really isn’t – read this guide on how to write poetry for beginners to learn the basics and start putting together your first poem or improving what you have already written.

Once you start, you’ll realise that not only is writing poetry fun, it is also a wonderful form of self-expression and can be extremely cathartic.

As a beginner poet, you can just dive straight in and start putting words on the page.

And, if you are creative in some way, whether you write long-form prose, create intricate drawings or take inspirational photographs, you may feel more confident than most at turning your hand to verse.

I can’t promise you’ll have a great gift for it, but – and here’s the joy of poetry – it doesn’t matter.

Write complete drivel if it helps you to get your feelings out because that is poetry’s primary purpose: to put into words something you need to express; to paint a metaphorical picture of something you’re dying to describe.

And if you’re stuck on the next scene of your novel, tackling a poem can get you back into the writing flow. So, if you are just a beginner with poetry the most important thing is to simply start writing something.

Of course, a stage or two on from the simply descriptive is the poem that offers something else: that suggests it may appear to be only about an orange, whilst it is also about ethnic cleansing or the trials of parenthood.

And that’s another matter: don’t feel you have to write about the great social injustices (such as ethnic cleansing).

Arguably as artists we may have a duty to attempt to tackle some of these.

But the everyday has its own politics, from the fears of being a single parent to the desperation that seizes you when you realize you’ve eaten an entire packet of chocolate digestives.

Either way, a good poem will offer a universal truth: some insight or alternative viewpoint on something profoundly political or resolutely banal.

Good poetry will also eschew the adverbs I’ve thrown heavy-handedly (there’s another one) into this post.

This is for two main reasons: firstly, because a good poem will rely on strong verbs and nouns to say all that is necessary, without requiring modification by adverbs; and, second, because an adverb can take up unnecessary space, which can make fine-tuning the rhythm of the poem harder.

The beauty of writing poetry is that you can start – and finish – a piece within a matter of days.

Sometimes a poem will almost write itself. I write novels and stories as well as poetry, and I find the latter gives me the near-instant gratification that is sorely lacking in the former.

However, if you were taught badly in school, or if you’ve simply never tried to write a poem, the idea can be a daunting prospect.

Here are some simple poetry exercises for beginners, to show how easy it can be to get from an idea to a poem-in-progress. I’m covering the theme of ‘Loss’ in this mini-workshop – but don’t worry if that sounds too emotional for you – we’re tackling the loss of an object, not a human being or your family pet (although you can, of course, cover either or both of those, should you choose).

How to Write Poetry for Beginners Mini-Workshop

Let’s start with an object you would be sorry to lose. (Or one you have lost, if you can still remember how it looked and felt.)

1) Describe the object

Use single words or phrases to describe it. Don’t search for fancy metaphors and similes at this stage.

If it’s a blue pen, then you might write: ‘Blue, cylindrical, long, slim, silver clip, shiny, neat’. If you still have it, then pick up your item and test how it feels. Is it ‘light’ or ‘surprisingly heavy’? Is it ‘rough’ or ‘smooth’?

2) Find a more interesting way to phrase the descriptions on your list

- ‘Blue’ could become: ‘the colour of your eyes’ (see how we’re already introducing another person into the poem. We’re also no longer stating the actual colour – so it could refer to anyone).

- ‘Slim’ could be: ‘fragile between my fingers’. (Remember, you don’t have to be literal. This is about expressing a sensation, so that the reader relates to the subject.)

- Of the ‘silver clip’: ‘snatching at my pocket cuff with its/your slim finger’.

This is the point where you can play around a bit. Who are you addressing? Is it the object (in this case, the pen), or a third person (the one with eyes the same colour as the item)?

3) Make it more interesting

Consider unlikely ways to use your item. If it’s a pen, what would it feel like if you swallowed it? [Ed’s note: please don’t take this literally.] How would it taste on the tongue? Would it leak ink like blood as it passed through your body?

4) If you already have a person in your piece, then you have the beginning of a poem

It is no longer just about a pen but is also now about a relationship. How specific you are about that relationship is up to you. If you are still only on the object, then consider what other relevance that item could have.

If it’s a ring, then relationships are suggested immediately. Play with these.

If it’s a penknife, was it a secret that you smuggled into school? Did it suggest your own desire, even then, to defy authority?

The music on an iPod could be the music a partner chose for you – or perhaps it’s the iPod of a child who’s left home or has been lost in some other, more tragic way…

What next?

Once you’ve written a few poems as a novice, you may feel ready to take your poetry to the next level. This usually means seeking out a readership or an audience – however small. To be successful at this, you’ll probably need to think a little more closely about what you’re doing and why you’re doing it.

Why a poem?

When you’re ready to write something, this ought to be your first question before you put pen to paper or fingers to keyboard. It means you need to know why you are choosing to put your idea into a poem rather than, say, a short story or flash fiction. There is no right answer to this question and sometimes poetry and prose can seem almost indistinguishable. However, there are several common differences.

A poem…….

- is as much about the aesthetics of the language as the ideas it contains

- is usually metrical, which means it is written in a structured or formal manner

- uses the positioning of the words on the page to help convey the meaning

- takes its name from a word deriving from a Latin term, meaning “poet”

Prose…….

- is a means of conveying information, ideas or a story

- does not use metre, line breaks, rhythm or rhyme

- usually contains a single idea in a single sentence

- is a word deriving from a Latin term, meaning “straightforward”

Structure and form

Once you’re sure that a poem is the right vehicle for your idea, you’re ready to begin the creative process. As an absolute beginner, you can concentrate solely on putting words on the page but, as your confidence grows, you may want to experiment with how you arrange the words.

Line length and line breaks

Unlike a piece of prose, where the position and place of the words on the page depends on the paper size, the margins and the font, the words that form a poem remain in the same place.

This is because line lengths and line breaks are inherent to any poem, affecting how a reader reads it or a listener hears it.

Line breaks, in particular, can be used to great effect to emphasise ideas or follow a rhythm (more on this later). Even novices tend to pause slightly at the end of a line of poetry.

Readers may also unconsciously adjust their speed of reading depending on how many words are in a line and perhaps also due to how much white space surrounds the poem.

Finally, there is a natural tendency to ascribe greater significance to the words that appear at the end of a line or have a whole line to themselves.

Capitalisation

Traditionally each new line of a poem begins with a capital letter but modern poets are increasingly choosing to break with this practice.

As with many things to do with poetry, there is no right or wrong answer. Sometimes, capitalising each line can affect the flow of the poem or appear a little “shouty”.

In other poems, line capitalisation may fit well with the rhythm of the piece. As a poet, it is your choice whether to capitalise each line, to capitalise each new sentence or to do away with capitals altogether.

The key is to be consistent and to know why you’re doing what you’re doing.

Dispensing with line capitalisation halfway through a poem can be confusing for the reader.

Similarly, if you choose to capitalise a particular word, especially if it’s in the middle of a line or sentence, you need to know why you’re doing it and what effect you want to achieve.

For example, you may choose to capitalise a particular word in order to draw the reader’s attention to it. Remember, however, that if you are writing a poem that is intended to be spoken, rather than read, capitalisation may not have quite the effect you are hoping for.

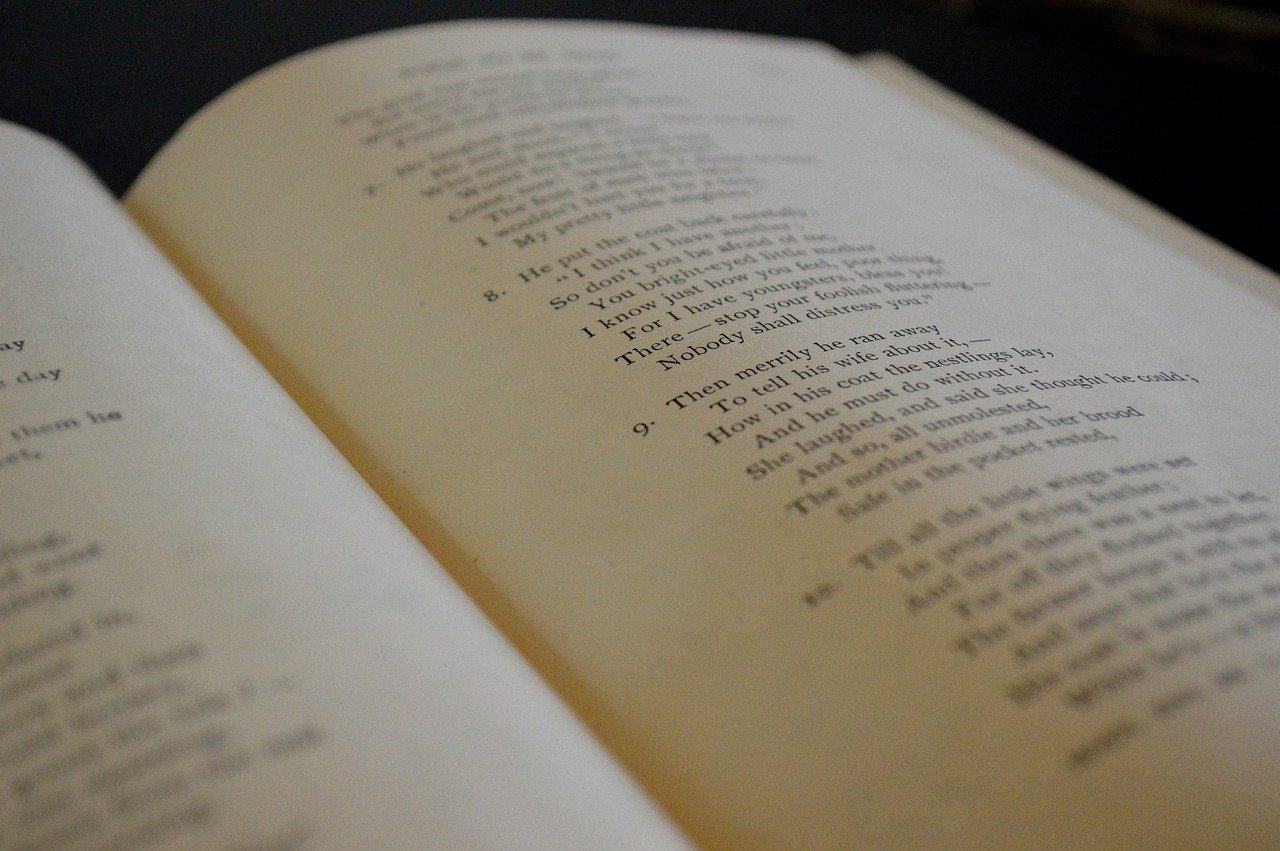

Rhymes and rhyme schemes

Once upon a time, there was a belief that a poem was only a poem if it rhymed. To some extent, this misconception still exists, and you may have come across it in school.

The fact is that a poem no more needs to rhyme than it needs to be about a particular topic. It can rhyme, of course, but that is a decision for you, as the poet.

Usually, if we say that a poem rhymes, we mean that the last syllables at the end of a line share the same sounds as the syllables at the end of another line. For example: night and delight.

Occasionally, a poet uses only one rhyme in a stanza (the proper name for a verse) but most rhyme schemes are a little more complex.

To explain the structure of a rhyme scheme, each rhyming pair of words is given a letter of the alphabet.

Consequently, in a four-line stanza where the first and third lines rhyme, and the second and fourth rhyme, the rhyme scheme would be: ABAB. If the first and second lines rhymed, while the third and fourth shared a different rhyme, the rhyme scheme would be AABB. Each new rhyming word is given a new letter of the alphabet.

There are also several other rhyme possibilities. For example, sometimes internal rhymes are used, where a word in the middle of a line rhymes with the word at the end.

Metre

If you have distant school day memories of feet or have an inkling of what iambic pentameter is, you are thinking about metre.

Essentially, metre is the rhythm of a poem – and it boils down to the number of syllables used, and to the stresses we naturally lay on some syllables and not others when we speak.

There is a rhythm to everything you say and write, even if it is not regular and even if you didn’t plan it.

Poems, on the other hand, are often written to a formal rhythm, or metre, which link individual rhyming units, known as “feet”.

Perhaps the most famous example in the English language is Shakespeare’s use of that iambic pentameter mentioned above.

A foot becomes an iamb if it consists of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed one. Put five iambs together and you have a line of iambic pentameters, such as: “If music be the food of love, play on”.

To begin with, you might want to try and work to a regular metre but poets often play around with the rhythm, putting in extra feet or altering the stress patterns.

If you’re interested in learning more about metre or any other poetic terms, the Poetry Foundation is a superb online resource

Reading out loud

It’s easy to get hung up on rhythm and metre (especially if you aren’t quite sure what they are or how to achieve the effect you want).

However, a great way for any poet to tell whether their poem flows well is to read it out loud.

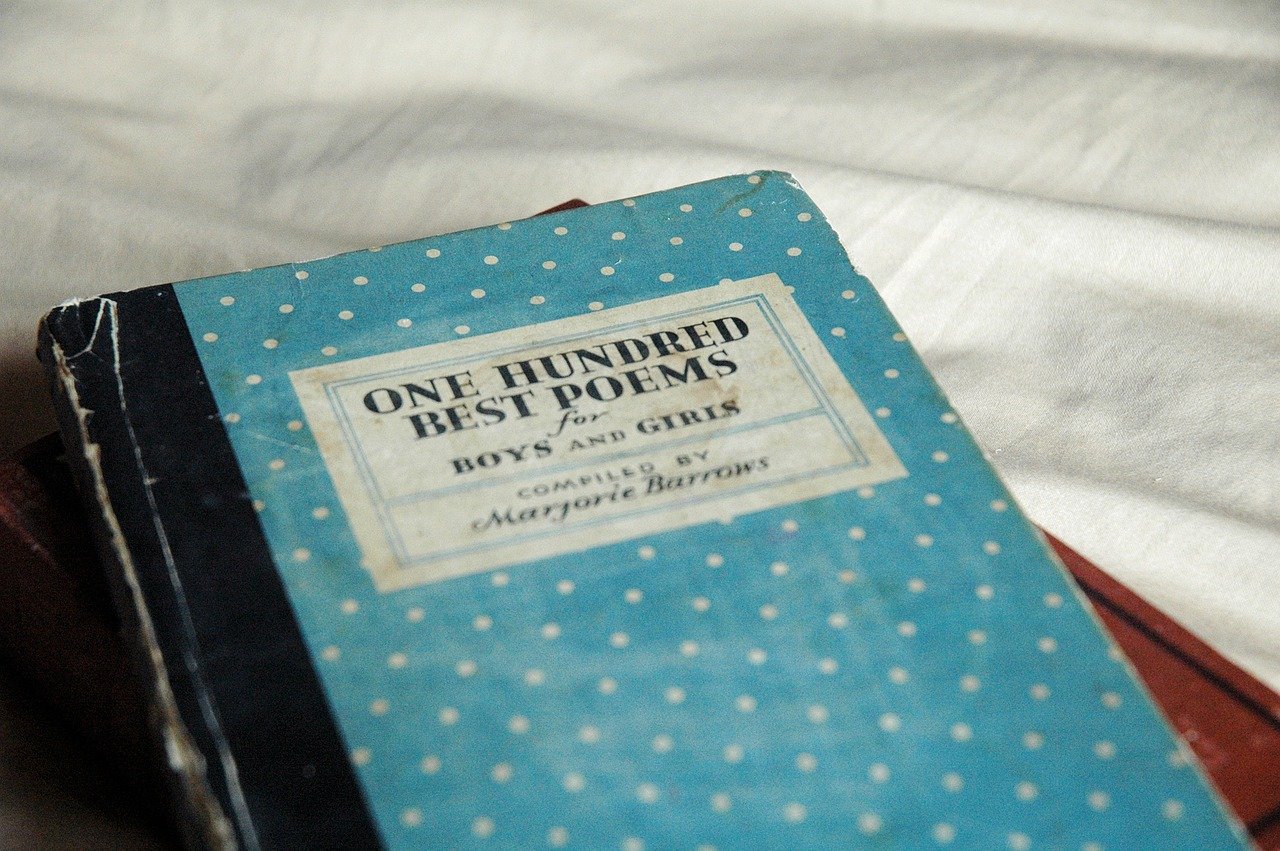

The importance of reading other poets

Most poets would emphasise that it is not possible to write good poetry without reading, and listening to, other people’s poetry.

Wendy Cope, for example, has some interesting points to make on the subject; as she says, it is difficult to imagine an amateur musician who does not like listening to music or an amateur painter who does not appreciate art galleries.

And, yet, it is common to come across would-be poets who claim not to read other people’s poetry.

Perhaps this avoidance stems from a fear of being unduly influenced or perhaps it is through ignorance or arrogance. Whatever the reason, it is misguided.

Reading other poets does not have to mean starting with the “Greats” – Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth and the like – although these are all excellent choices and, arguably, no poetic education is complete without some knowledge of these writers.

However, one of the wonderful things about poetry is its diversity: W.H. Auden, Ted Hughes, Simon Armitage, Carol Ann Duffy, Benjamin Zephaniah and Pam Ayres are all wildly different but no less valid for that.

As well as poets who win Forward Prizes and feature on the shelves of Waterstones, there are poets who write on Facebook, poets who perform on YouTube and poets who get up in their local pub.

The important bit is to read as many of them as possible in order to work out why they are (or, sometimes, are not) good at what they do and how they make it work. And, of course, you might well find yourself a new favourite poet.

Writing “in the style of”…..

One of the near-inevitable results of reading poetry is that you begin to mimic the style of your favourite poets.

This is natural and not, at first, something to worry about. Just as with any other artist, poets have a great deal to learn from emulating those working at the peak of the craft.

The key is, in time, being able to move on from your Sylvia Plath or W.B. Yeats phase and find your own voice.

Getting your poetry out there

It isn’t essential – after all, Emily Dickinson wasn’t “discovered” until after her death – but gaining some sort of readership is an important validation for many poets, particularly as they progress with their writing.

Submitting to publications

The idea of “submitting” one of your poems to a publication can be daunting. Starting small is often the way to go.

A wealth of publications, both hard copy and online, now welcome poetry submissions. Some are very prestigious, accepting only a tiny proportion of submissions.

Others, especially smaller or local publications, are more accessible.

Twitter is an excellent way of keeping an eye on which publications are open for submissions, and for gleaning inside knowledge on what their editors like.

Before submitting anything, it is important to understand what your target publication is looking for. It might sound obvious but this means you have to read it.

One of most editors’ biggest gripes concerns writers submitting inappropriate material. Always ask yourself whether what you want to submit fits with what the publication prints.

When looking at submission guidelines, you might see something about “simultaneous submissions”.

This means submitting the same poem/s to more than one publication, at the same time. Some publications don’t like this; they want you to submit those particular poems only to them, and to wait for a response before submitting the same poetry elsewhere.

This is all well and good but, given that it is not unusual to have to wait up to six months before hearing back from a publication, you might end up with poems “in limbo” for rather a long time.

Some editors allow you to withdraw a poem from consideration if it’s accepted for publication elsewhere, and you may want to focus on these publications – at least until you’ve built up a good-sized portfolio.

Do remember to keep track of which poem you’ve sent where, and when. Sending a previously rejected poem to the same publication is embarrassing but a good spreadsheet will obviate the problem.

Although many publications are happy to receive several poems from the same poet, most will want them to be contained within the same submission.

As a rule, multiple submissions are not welcomed. If the submission guidelines state no multiple submissions, make sure you send only the one submission.

The guidelines should state how many poems you are allowed to include in one submission and when you are allowed to make another submission (it is not uncommon to be restricted to a single submission every six months or so).

Some organisations, including the very prestigious Poetry Society, may require paper submissions.

Those publications that do accept emailed submissions usually prefer to receive submissions in a single Word file.

Whatever the requested format, make sure you start each poem on a new sheet and check the individual publication’s guidelines, to see whether you should avoid having your name on the poems themselves.

Similarly, if the guidelines request a short bio, make sure you include one and make sure it’s within the maximum word count.

Competitions

As with publications, these vary from large and prestigious, to smaller affairs. Big national or international competitions may attract thousands of entries.

Smaller, local competitions are a better way of getting started. Writing magazines often contain listings for competitions as well as running their own contests.

Local newspapers also sometimes also run contests. It is standard for many competitions to charge an entry fee.

Sometimes entrants can choose to pay an additional sum in order to receive a critique of their poem, regardless of whether or not it wins a prize.

What makes a prize-winning poem is an elusive question. It can help to know who the judges are and what sort of poetry they like. Usually poets themselves, the style of a judge’s own poetry may offer a not-so-subtle hint.

Reading judges’ reports can provide further clues as to why a particular poem was successful and, even more pertinently, why so many others did not make it to long listing, short listing or the final roll of winners.

Often this will be to do with technical strength. A faltering rhythm or forced rhyme scheme, even if this only happens once or twice within a poem, may be all it takes for an otherwise excellent piece to fall out of contention.

Equally, a poem that is beautifully written and full of evocative imagery may not even make the long list if it does not also share some sort of “truth” or message. Finally, something more than one competition judge has noted, is the importance of a poem’s title.

It is a delicate balancing exercise between intriguing someone enough to read on and giving too much away. Some poets are better than others at naming their poems. In general, using the first line as the title is a cop-out but doing as novelists sometimes do and “reading for title” can yield a phrase that works well.

Open mic nights, poetry slams and other ways of meeting fellow poets

A very valid addition or alternative to seeking publication is to take your poems to one of the many open mic nights.

Varying in format and atmosphere, these often feature a “billed” poet – who can be very well-known – before the floor is opened up to anyone else who wants to read.

All you’ll need to do is to arrive in time, give your name (and possibly an entrance fee) to the host, and wait to be called to read. You’ll usually be given a maximum time span (hint: a 40 line poem should be all right but an epic on the scale of The Wasteland almost certainly will not); try to find out what it is beforehand and practice your reading to be sure it fits within the allocated slot.

Your first open mic night can be nerve-wracking but most events are welcoming and supportive of newcomers. Poetry slams, on the other hand, are competitive, with judges scoring each poem. It may be best to wait until you are confident both in your poems and in performing them out loud to an audience before participating in a slam.

If you’re in the UK, the Poetry Café, in London’s Covent Garden, hosts all kinds of poetry readings, book launches and related events. Run by the Poetry Society, it is a great place to go and meet like-minded people. The Poetry Society is also a useful resource for anyone looking for practical help to improve their poetry.

Similarly, the London-based Poetry School offers face-to-face and online courses. The Poetry School is also the host of CAMPUS, an online platform designed to bring together poets from across the world, whether beginners or professionals.

Formatting and font

Double line spacing is not really necessary for poetry, the way it is for stories and novels.

Most poets use single line spacing, although 1.5 is generally also acceptable. Unless your poem has a “concrete” structure – whereby the physical shape of the poem refers to its subject matter – then align left.

Most poets would usually put a large left-hand indent on my poems, so that they are fairly central on the page, but this is a matter of personal preference.

Finally, as with any formal or professional document, forget interesting fonts and colour choices. Times New Roman, Arial, Calibri, Helvetica or, if you must, Garamond, are the best font choices.

If in any doubt, err on the conservative side; you don’t want an editor rejecting your submission because they were distracted by your choice of font. Font colour, it ought to go without saying, should be black.

Different poetic forms

The more time you spend reading poetry, the more you will come across the many different forms of poetry.

And the more time you spend writing poetry, the more confident you will feel about trying some of them for yourself. Here are some of the most popular:

- Blank verse – Almost always written in iambic pentameter, this is a form of unrhymed poetry that is widely used in dramatic and epic works written in English. Its popularity probably stems from how closely it resembles the patterns of natural speech.

- Sonnet – Originally an Italian invention, there are many different types of sonnet. Meaning “little song”, a sonnet is a short poem, usually of 14 lines. There are several different types, most famously including the Petrarchan and Shakespearean sonnets. They adhere to a formal rhyme scheme and are traditionally written in iambic pentameter.

- Sestina – An intricate poem, which is French in origin, a traditional sestina consists of five unrhymed six-line stanzas, finished with a three-line “envoi”. The six different words that end each line of the first stanza must also end a line in each of the other stanzas – and there is an accepted pattern for the repetition. The envoi must include each of the six end words, with one appearing in the middle of each line and one at the end. If this sounds complicated, that’s because it is but, on the upside, writing your first sestina is immensely satisfying and a landmark moment for most new poets.

- Haiku – This three-line Japanese poem probably requires little introduction. Adhering to a 5-7-5 syllable rhythm, its lines are unrhymed and often focus on nature.

Submitting your poems for the first time

Many publishers talk about ‘simultaneous submissions’. This means submitting the same poem/s to their publication as to another publication, at the same time.

If they don’t like simultaneous submissions, they want you to submit those particular poems only to them, and to wait for a response before submitting the same poetry elsewhere.

Multiple submissions: If the publisher states they don’t like multiple submissions, then send only the one submission (their guidelines should state how many poems you are allowed to include in one submission). Wait to hear from them before sending them anymore.

Incidentally, a lot of publishers like to have your submission in one Word file. Make sure you start each poem on a new sheet and check the individual publication’s guidelines, to see whether you should avoid having your name on the poems themselves.

Double line spacing: not really necessary for poetry, the way it is for stories and novels. I’d use single line spacing. Unless your poem has a ‘concrete’ structure – whereby the physical shape of the poem refers to its subject matter – then align left.

However, I would usually put a large left-hand indent on my poems, so that they are fairly central on the page.

If you are a poet be sure to submit your work to The Talent Bank.

How to Write Poetry For Beginners: Easy if You Know How

How to Write Poetry For Beginners: Easy if You Know How The Best Acoustic Guitars in the World

The Best Acoustic Guitars in the World 9 Super Creative Street Art Pieces

9 Super Creative Street Art Pieces The 10 Greatest TV Shows of All Time

The 10 Greatest TV Shows of All Time How to Play Guitar for Beginners

How to Play Guitar for Beginners

Very thorough! A great overview.